荨麻疹

引文参考:

中华医学会皮肤性病学分会免疫学组. 中国慢性诱导性荨麻疹诊治专家共识(2023)[J].中华皮肤科杂志,2023, 56(6):479-488. doi:10.35541/cjd.20220819

【摘要】 慢性诱导性荨麻疹是一组由特定诱因诱发、以风团和/或血管性水肿为主要临床表现的慢性荨麻疹,可伴有瘙痒、刺痛、烧灼、疼痛等不适症状。该病临床表现异质性大,病情迁延反复,对患者生活质量影响较大。为提升我国临床医生对该病的认识,规范疾病诊治行为,中华医学会皮肤性病学分会免疫学组基于近年来国内外关于慢性诱导性荨麻疹诊断和治疗的临床研究进展,通过德尔菲法广泛征询专家意见,并经相关专家多轮讨论,最终形成本共识。

【关键词】 荨麻疹;慢性诱导性荨麻疹;皮肤划痕征;冷接触性荨麻疹;胆碱能性荨麻疹;诊断;治疗;专家共识

DOI:10.35541/cjd.20220819

Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inducible urticaria in China (2023)

Immunology Group, Chinese Society of Dermatology

Corresponding authors: Song Zhiqiang, Email: [email protected]; Gu Heng, Email: [email protected]

【Abstract】 Chronic inducible urticaria is a group of chronic urticaria induced by specific triggers, with wheal and/or angioedema as main clinical manifestations, which may be accompanied by itching, tingling, burning sensation, pain and other unpleasant symptoms. This group of diseases are characterized by highly heterogeneous clinical manifestations, long courses, and recurrent symptoms, which have a great impact on the quality of life of patients. Based on progress in Chinese and international clinical studies on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic inducible urticaria in recent years, the Immunology Group of Chinese Society of Dermatology extensively consulted experts through the Delphi method, and finally developed this consensus after several rounds of discussion among relevant experts, in order to improve clinicians' understanding of this group of diseases and standardize their diagnosis and treatment.

【Key words】 Urticaria; Chronic inducible urticaria; Symptomatic dermographism; Cold contact urticaria; Cholinergic urticaria; Diagnosis; Treatment; Expert consensus

DOI: 10.35541/cjd.20220819

慢性荨麻疹分为慢性自发性荨麻疹(chronic spontaneous urticaria,CSU)和慢性诱导性荨麻疹(chronic inducible urticaria,CIndU)。CIndU是一组由特定诱因(冷 、热、运动、压力、阳光、振动、水等)诱发、以风团和/或血管性水肿为主要临床表现的荨麻疹。相比于CSU,CIndU发生的诱因明确,但其病因不明,发病机制复杂。CIndU存在多个类型和更多细分亚型,临床表现异质性强,病情迁延反复,对患者生活质量影响较大。

一直以来国内对该疾病关注度偏低,尤其是广大基层皮肤科医生对其缺乏全面深入的了解,诊治行为不够规范。目前全世界仅欧洲过敏与临床免疫学会曾发布过CIndU的共识,但已6年未更新[1]。我国尚未有针对CIndU的诊疗指南或共识。为提升临床医生对CIndU的认识,规范CIndU的诊治行为,中华医学会皮肤性病学分会免疫学组在总结国内外CIndU诊疗研究进展的基础上,基于德尔菲(Delphi)专家问卷咨询法广泛征询专家意见,并经相关专家多轮讨论,最终形成了本共识[2]。

一、流行病学

目前关于我国人群CIndU的流行病学研究报道较少。2014年一项基于我国医院就诊患者群体的多中心临床流行病学研究结果显示,CIndU占慢性荨麻疹的31.9%(其中物理性荨麻疹占29.3%,非物理性荨麻疹占2.6%),最常见类型依次为皮肤划痕征(也称人工荨麻疹,20.9%)、冷接触性荨麻疹(3.0%)、胆碱能性荨麻疹(2.6%);在性别分布上,冷接触性荨麻疹和延迟压力性荨麻疹更常见于女性,而胆碱能性荨麻疹则好发于年轻男性[3]。在年龄分布上,有文献报道65岁以上人群CIndU的患病率低于65岁以下人群和14岁以下儿童群体[4]。2022年一项基于我国普通人群的流行学问卷调查显示,CIndU的人群终生患病率为1.3%[5]。国外报道普通人群CIndU的患病率为0.1% ~ 5.0%,最常见的类型与我国人群CIndU的流行病学特点一致[6]。

二、病因与发病机制

与CSU相似,CIndU的病因常难以明确。研究显示,CIndU的发生可能与遗传、特应性背景、感染、血液系统疾病、自身免疫性疾病、药物、疫苗、免疫治疗、昆虫叮咬或水母刺伤、文身、精神压力、饮食、胃肠道菌群异常等多种因素相关[7-13]。例如,水源性荨麻疹和振动性荨麻疹患者存在多个基因突变位点[7-8];胆碱能性荨麻疹和冷接触性荨麻疹均有高比例的特应性背景[9,14];丙型肝炎病毒、HIV、EB病毒、弓形虫等感染可能与冷接触性荨麻疹发病相关[14];安非他酮和氯米帕明可诱导水源性荨麻疹[8],而青霉素、短效避孕药、血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂、灰黄霉素等可诱导冷接触性荨麻疹[14];骨髓增生异常综合征、多发性骨髓瘤、淋巴增生性疾病、T细胞非霍奇金淋巴瘤、嗜酸性细胞增多综合征等可能与冷接触性荨麻疹、延迟压力性荨麻疹和水源性荨麻疹的发病相关[8,14-15];脑膜炎球菌疫苗、甲型肝炎疫苗、肺炎链球菌疫苗、H1N1流感疫苗等可诱导冷接触性荨麻疹[10]。

CIndU的确切发病机制尚不完全清楚,但基本可以明确皮肤肥大细胞的激活和脱颗粒是CIndU发病的核心环节。既往研究显示,胆碱能性荨麻疹存在自体汗液过敏现象[16],而日光性荨麻疹患者中存在自身过敏原特异性IgE[17],且CIndU患者血清总IgE水平和嗜碱性粒细胞膜表面IgE高亲和力受体(FcεRⅠ)表达水平均明显升高[18],这些证据提示Ⅰ型自身免疫机制(又称自身过敏机制,autoallergy)可能是 CIndU发病的重要机制之一,推测各种物理和非物理因素刺激诱导机体释放或产生自身过敏原,后者与皮肤肥大细胞上自身过敏原特异性IgE结合并诱导交联,从而诱导肥大细胞活化和脱颗粒[19]。另外,其他不同的机制也可能参与不同类型CIndU的发病,如:Ⅱb型自身免疫机制可能参与冷接触性荨麻疹和胆碱能性荨麻疹的发生[14,16];Ⅲ型超敏反应、系统炎症激活和自身炎症机制在延迟压力性荨麻疹的发病中可能更为重要[20];神经源性通路调节的异常(如感觉神经系统和自主神经系统失调及其诱发的皮肤神经源炎症)在冷/热接触性荨麻疹、振动性血管性水肿、胆碱能性荨麻疹、水源性荨麻疹等发病中是不可忽略的重要机制[7-8,14,16,21];汗孔堵塞和出汗异常(如无汗症)是部分胆碱能性荨麻疹少见亚型发病的关键因素[16];外源性过敏原特异性IgE介导的Ⅰ型超敏反应以及外源性物质通过非免疫途径直接诱导肥大细胞活化是接触性荨麻疹发生的两个主要机制[22];离子通道如钠离子通道的缺陷参与水源性荨麻疹的发生,瞬时受体电位M型-8阳离子通道(TRPM8)参与冷接触性荨麻疹的发生[8]。了解不同发病机制在CIndU发病中的作用,有利于理解疾病表现和制定具有针对性的治疗方案。

三、临床表现与分型

CIndU主要表现为诱因暴露后出现风团和/或血管性水肿,可伴有瘙痒、刺痛、烧灼、疼痛等不适症状。除延迟压力性荨麻疹,绝大部分CIndU均在诱因暴露后数分钟内出现症状,去除诱因后,症状多在0.5 ~ 1 h 内自行消退,消退普遍快于CSU。患者一般仅有皮肤症状,极少数可出现严重过敏反应(anaphylaxis),部分延迟压力性荨麻疹患者可能出现发热、关节痛、乏力、头痛等全身症状。大部分类型的CIndU可合并出现血管性水肿,其中振动性荨麻疹、人工荨麻疹、胆碱能性荨麻疹等类型发生的比例较高[23-24]。同一例患者可能同时存在两种或两种以上类型的CIndU。超过1/3的CSU合并CIndU,其中最常合并的类型是人工荨麻疹[25]。

根据诱因不同,将CIndU分为物理性和非物理性荨麻疹两大类。物理性荨麻疹包括皮肤划痕征、延迟压力性荨麻疹、冷接触性荨麻疹、热接触性荨麻疹、日光性荨麻疹、振动性血管性水肿;非物理性荨麻疹包括胆碱能性荨麻疹、水源性荨麻疹、接触性荨麻疹[26]。各个CIndU类型有各自的临床特点,有些CIndU类型各自又可进一步细分为不同的亚型,详见表1。临床分类分型的细化有助于疾病的精准管理。

四、诊断与临床评估

(一)疾病诊断:CIndU的诊断主要根据病史和诱因激发试验。患者的病史和症状描述是重要的诊断线索,但临床医生需对患者提供的信息进行客观判断,避免盲信或仅凭患者病史和主诉做出诊断,有条件时应尽量依据激发试验来确定诊断。目前针对所有CIndU类型均已有相对成熟的诱因激发试验,同时也有一些专业的设备用于诱因激发试验的量化和标准化,如针对皮肤划痕征的校准皮肤划痕仪和皮肤划痕测试板(FricTest)[27]、针对冷/热接触性荨麻疹的温度测试仪(TempTest)[28]等。CIndU诱因激发试验具体操作见表2。需要注意的是,在进行CIndU的诱因激发试验前3天需停用抗组胺药,1周前需停止使用系统糖皮质激素。

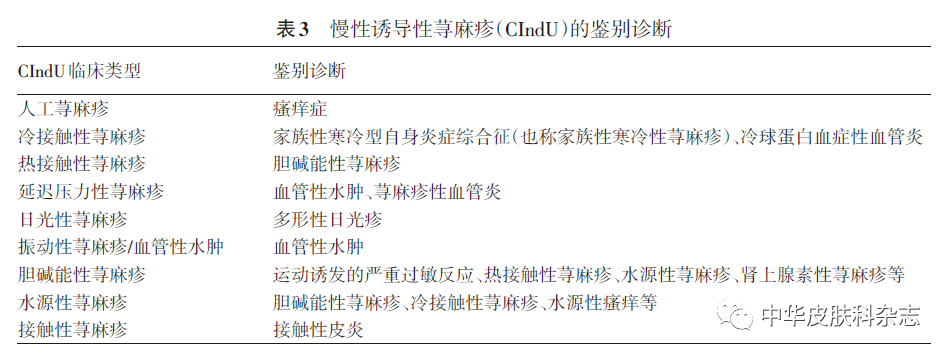

(二)鉴别诊断:根据患者病史和必要的激发试验,多数CIndU可相对明确地建立诊断,但不同类型CIndU需要与其他疾病或者其他类型CIndU进行鉴别。见表3。

(三)病情评估:主要包括疾病状态(疾病活动度和疾病严重程度)及患者生活质量评估。已经报道用于CIndU临床评估的工具见表4。鉴于目前针对CIndU部分类型的特异性评估工具尚未汉化,推荐临床医生根据实际情况, 在有条件的情况下尽量使用已经汉化的专业工具对CIndU患者进行定期临床评估,比如荨麻疹控制评分量表(UCT)、慢性荨麻疹生活质量问卷(CU-Q2oL)、皮肤病生活质量指数(DLQI)等。

另外,将CIndU的诱因激发试验的反应程度和激发阈值进行量化,也可作为疾病严重程度的评估工具。比如校准皮肤划痕仪和FricTest可以量化皮肤划痕征的相对压力激发阈值和反应程度[27],TempTest可以量化冷/热接触性荨麻疹的温度激发阈值[28],最小风团量可确认日光性荨麻疹的光激发阈值[40],脉冲控制运动试验可以量化评估胆碱能性荨麻疹的运动激发阈值等[41]。

(四)实验室检查:CIndU与其他疾病鉴别存在困难,或高度怀疑有潜在基础疾病时,可完善相关实验室检查。冷接触性荨麻疹与冷球蛋白血症性血管炎的鉴别可完善冷球蛋白、冷凝集素、补体检测等,针对高危病史患者可完善丙型肝炎病毒相关检测。针对延迟压力性荨麻疹鉴别诊断困难时可完善皮肤病理检查。鉴别接触性荨麻疹和接触性皮炎可进行(开放性)皮肤斑贴试验。超过半数的胆碱能性荨麻疹患者合并有特应性背景,且患者特应性背景与疾病严重程度和生活质量相关[9],因此对于有明确过敏病史的胆碱能性荨麻疹患者,可完善过敏原IgE及总IgE检测。不建议常规对CIndU患者进行大范围的实验室检查。

五、治疗

CIndU总体治疗原则是有效规避诱因,积极对症治疗。

(一)规避诱因:有效规避诱因对控制CIndU十分重要,应根据诱因激发试验的结果和对应的阈值,指导患者尽量避免相应的诱发因素。见表5。

(二)对症治疗:多数诱因在日常生活中常见,患者无法有效避免,故对症治疗是CIndU疾病管理的重要手段。根据已有的循证证据,CIndU治疗流程见图1。

1. 一线治疗:推荐二代抗组胺药作为CIndU的一线治疗选择。最新的系统综述显示,阿伐斯汀、西替利嗪、卢帕他定、地氯雷他定等二代抗组胺药在CIndU的治疗中具有更多的证据积累[42]。通常首先按照常规剂量用药,如果常规剂量治疗1 ~ 2周后效果不佳,可考虑更换其他品类,或两种不同的二代非镇静抗组胺药按常规剂量联合使用[43],必要时可以联合第一代抗组胺药;或者在获得患者知情同意的前提下,将第二代抗组胺药加量至2 ~ 4倍剂量,有效后逐渐减量维持[44]。不同类型CIndU对二代抗组胺药的治疗反应差别较大,其中皮肤划痕征治疗反应最好,无汗和/或少汗型胆碱能性荨麻疹和振动性血管性水肿对二代抗组胺药治疗反应较差[7,31]。

2. 二线治疗:对一线治疗抵抗者,在与患者充分沟通的情况下,推荐将抗IgE单克隆抗体作为二线治疗选择。奥马珠单抗(omalizumab)是一种结合游离IgE的人源化IgG1κ单抗,目前已被批准用于治疗H1抗组胺药治疗后仍有症状的成人和青少年(12岁及以上)CSU患者。临床研究显示,奥马珠单抗对大多数CIndU类型也有效[19,45]。根据英国牛津大学循证医学中心证据分级和推荐标准[46],奥马珠单抗治疗不同类型CIndU的证据级别和推荐意见见表6。除此之外,振动性血管性水肿仅有个案报道,提示对奥马珠单抗治疗反应差[54],尚无接触性荨麻疹接受奥马珠单抗治疗的报道。奥马珠单抗治疗CIndU的起效时间从24 h到4周不等,人工荨麻疹的治疗反应最快,而胆碱能性荨麻疹和冷接触性荨麻疹的反应较慢,大部分患者维持治疗24周时达到最佳反应率[55]。关于奥马珠单抗在治疗CIndU中如何减停尚无定论,本共识建议患者症状持续稳定至少6个月,再考虑逐渐减停。如果停药后症状复发,重新接受奥马珠单抗治疗仍有效[47]。

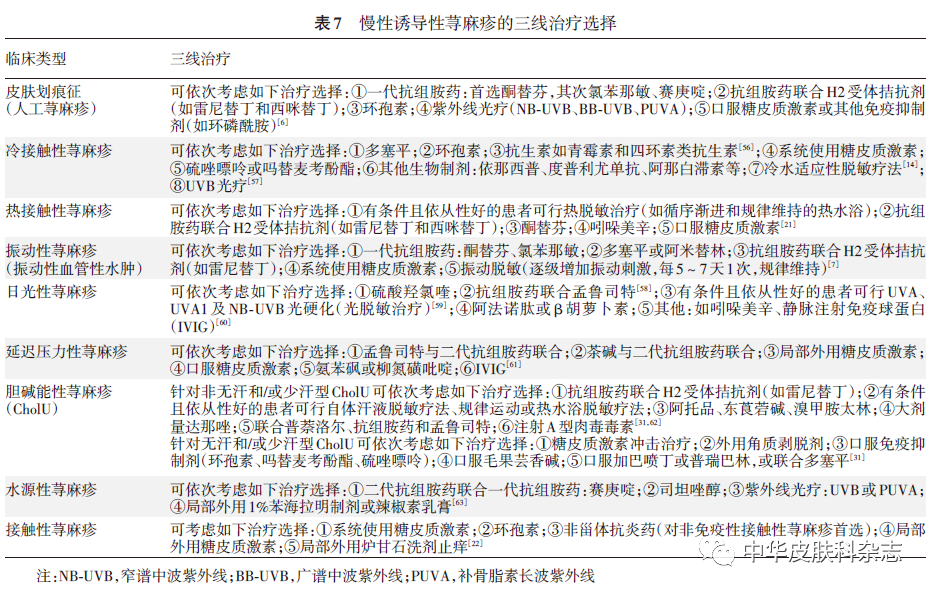

3. 三线治疗:对上述治疗无效者,可考虑三线治疗。由于三线治疗选择在不同CIndU类型差别较大,且证据级别不高。本共识基于现有临床研究报道的证据质量和治疗反应,并结合临床可操作性,对各类型CIndU的三线治疗药物的推荐进行排序(表7)。其中针对部分CIndU类型的诱因脱敏治疗,比如冷/热适应脱敏治疗、振动脱敏治疗、光硬化(光适应性脱敏)治疗、自体汗液脱敏疗法、运动或热水浴脱敏疗法等,对相应的CIndU类型均能取得不错的治疗反应。但此类治疗一般操作比较繁杂,且存在一定的诱导加重风险,患者长期坚持有一定难度,在临床实践中若计划进行此类治疗需要与患者充分沟通,以充分评估其可行性、依从性和总体获益。

少数患者如果突然出现症状和体征加重伴心血管症状(如心悸、血压下降等)和/或呼吸道症状(如憋气、呼吸困难等)时,要注意严重过敏反应的可能,应及时给予肾上腺素和/或短期系统使用糖皮质激素等急救处理。

六、自然病程

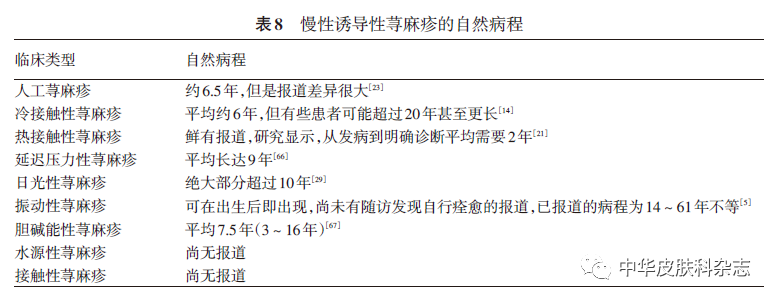

基于国外已有的相关报道,各CIndU之间在疾病自然病程上有一定差异。虽然大部分CIndU的病程都较长,但最终基本都会自行痊愈。整体而言,已报道成人物理性荨麻疹1年缓解率只有16.4%[64],而儿童CIndU的1年缓解率只有9.6%[65]。因此在临床管理过程中需要做好患者的健康教育,让患者有充分的心理预期,并建立长期配合治疗和疾病管理的理念。不同类型的CIndU自然病程有一定差异(表8)。

七、共识声明

所有参与本共识制定的专家均声明:秉承完全客观的立场,以专业知识、循证证据和临床经验为依据,严格按照德尔菲法收集并拟合意见,并通过充分讨论,全体专家一致同意后形成本共识。

八、免责声明

本共识的内容仅代表参与制定的专家对CIndU诊治的指导意见,供临床医师参考。尽管专家们进行了广泛的意见征询和讨论,但仍有不全面之处。疾病的治疗需要遵循个体化原则,本共识所提供的建议并非强制性意见,与本共识不一致的做法并不意味着错误或不当。临床实践中仍存在诸多问题需要探索,需要更多的临床和基础研究予以解答。随着CIndU临床与基础研究的不断进展、新的循证证据不断呈现以及临床经验的积累,未来需要对本共识定期修订、更新,进一步提升CIndU的管理水平。

参加本共识制定的专家名单(按姓氏笔画排序):

王刚(空军军医大学西京医院)、王芳(中山大学附属第一医院)、王建琴(广州市皮肤病防治所)、王惠平(天津医科大学总医院)、尹光文(郑州大学第一附属医院)、龙海(中南大学湘雅二医院)、孙青(山东大学齐鲁医院)、李邻峰(首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院)、李承新(中国人民解放军总医院)、李捷(中南大学湘雅医院)、肖汀(中国医科大学附属第一医院)、邹颖(上海市皮肤病医院)、宋志强(陆军军医大学西南医院)、陈奇权(陆军军医大学西南医院)、金哲虎(延边大学附属医院)、赵作涛(北京大学第一医院)、郝飞(重庆医科大学附属第三医院)、柏冰雪(哈尔滨医科大学附属第二医院)、姚煦(中国医学科学院皮肤病研究所)、晋红中(中国医学科学院北京协和医院)、顾恒(中国医学科学院皮肤病研究所)、徐金华(复旦大学附属华山医院)、高兴华(中国医科大学附属第一医院)、鲁严(江苏省人民医院)、曾抗(南方医科大学南方医院)、谢志强(北京大学第三医院)

参 考 文 献

[1] Magerl M, Altrichter S, Borzova E, et al. The definition, diagnostic testing, and management of chronic inducible urticarias - The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus recommendations 2016 update and revision[J]. Allergy, 2016,71(6):780-802. doi: 10.1111/all.12884IF: 14.710 Q1 .

[2] 陈奇权, 杨显杰, 顾恒, 等. 基于德尔菲法构建《中国慢性诱导性荨麻疹诊治专家共识(2023)》[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2023,56(6):534-539. doi: 10.35541/cjd.20220814.

[3] Zhong H, Song Z, Chen W, et al. Chronic urticaria in Chinese population: a hospital-based multicenter epidemiological study[J]. Allergy, 2014,69(3):359-364. doi: 10.1111/all.12338IF: 14.710 Q1 .

[4] Napolitano M, Fabbrocini G, Stingeni L, et al. Prevalence of chronic inducible urticaria in elderly patients[J]. J Clin Med, 2021,10(2):247. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020247IF: 4.964 Q2 .

[5] Li J, Mao D, Liu S, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in China: a population-based study[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2022,135(11):1369-1375. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002172IF: 6.133 Q1 .

[6] Kulthanan K, Ungprasert P, Tuchinda P, et al. Symptomatic dermographism: a systematic review of treatment options[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2020,8(9):3141-3161. doi: 10. 1016/j.jaip.2020.05.016.

[7] Kulthanan K, Ungprasert P, Tapechum S, et al. Vibratory angioedema subgroups, features, and treatment: results of a systematic review[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2021,9(2):971-984. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.009IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[8] Wang F, Zhao YK, Luo ZY, et al. Aquagenic cutaneous disorders[J]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2017,15(6):602-608. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13234IF: 5.231 Q1 .

[9] Altrichter S, Koch K, Church MK, et al. Atopic predisposition in cholinergic urticaria patients and its implications[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2016,30(12):2060-2065. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13765IF: 9.228 Q1 .

[10] Raison-Peyron N, Philibert C, Bernard N, et al. Cold contact urticaria following vaccination: four cases[J]. Acta Derm Venereol, 2016,96(6):852-853. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2358IF: 3.875 Q2 .

[11] Raison-Peyron N, Litovsky J, Huet P, et al. Cold contact urticaria triggered by a permanent tattoo[J]. J Cosmet Dermatol, 2021,20(8):2463-2465. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13874IF: 2.189 Q3 .

[12] Yücel MB, Ertas R, Türk M, et al. Food-dependent and food-exacerbated symptomatic dermographism: new variants of symptomatic dermographism[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2022,149(2):788-790. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.030IF: 14.290 Q1 .

[13] Liu R, Peng C, Jing D, et al. Identification of gut microbiota signatures in symptomatic dermographism[J]. Exp Dermatol, 2021,30(12):1794-1799. doi: 10.1111/exd.14326IF: 4.511 Q1 .

[14] Maltseva N, Borzova E, Fomina D, et al. Cold urticaria - What we know and what we do not know[J]. Allergy, 2021,76(4):1077-1094. doi: 10.1111/all.14674IF: 14.710 Q1 .

[15] Lawlor F, Black AK. Delayed pressure urticaria[J]. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am, 2004,24(2):247-258, vi-vii. doi: 10. 1016/j.iac.2004.01.006.

[16] Fukunaga A, Washio K, Hatakeyama M, et al. Cholinergic urticaria: epidemiology, physiopathology, new categorization, and management[J]. Clin Auton Res, 2018,28(1):103-113. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0418-6IF: 5.625 Q1 .

[17] Lugović Mihić L, Bulat V, Situm M, et al. Allergic hypersensitivity skin reactions following sun exposure[J]. Coll Antropol, 2008,32 Suppl 2:153-157.

[18] Giménez-Arnau AM, Ribas-Llauradó C, Mohammad-Porras N, et al. IgE and high-affinity IgE receptor in chronic inducible urticaria, pathogenic, and management relevance[J]. Clin Transl Allergy, 2022,12(2):e12117. doi: 10.1002/clt2.12117IF: 5.657 Q2 .

[19] Maurer M, Metz M, Brehler R, et al. Omalizumab treatment in patients with chronic inducible urticaria: a systematic review of published evidence[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018,141(2):638-649. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.032IF: 14.290 Q1 .

[20] Lenormand C, Lipsker D. Efficiency of interleukin-1 blockade in refractory delayed-pressure urticaria[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2012,157(8):599-600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00023IF: 51.598 Q1 .

[21] Pezzolo E, Peroni A, Gisondi P, et al. Heat urticaria: a revision of published cases with an update on classification and management[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2016,175(3):473-478. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14543IF: 11.113 Q1 .

[22] 刘鑫, 刘念, 陈宏翔. 接触性荨麻疹诊治进展[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2021,54(12):1114-1117. doi: 10.35541/cjd.20200079.

[23] Schoepke N, Młynek A, Weller K, et al. Symptomatic dermographism: an inadequately described disease[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2015,29(4):708-712. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12661IF: 9.228 Q1 .

[24] Mellerowicz EJ, Asady A, Maurer M, et al. Angioedema frequently occurs in cholinergic urticaria[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2019,7(4):1355-1357.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip. 2018.10.013.

[25] Sánchez J, Amaya E, Acevedo A, et al. Prevalence of inducible urticaria in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: associated risk factors[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2017,5(2):464-470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.029IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[26] Zuberbier T, Abdul Latiff AH, Abuzakouk M, et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria[J]. Allergy, 2022,77(3):734-766. doi: 10.1111/all. 15090.

[27] Schoepke N, Abajian M, Church MK, et al. Validation of a simplified provocation instrument for diagnosis and threshold testing of symptomatic dermographism[J]. Clin Exp Dermatol, 2015,40(4):399-403. doi: 10.1111/ced.12547IF: 4.481 Q1 .

[28] Magerl M, Abajian M, Krause K, et al. An improved Peltier effect-based instrument for critical temperature threshold measurement in cold- and heat-induced urticaria[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2015,29(10):2043-2045. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12739IF: 9.228 Q1 .

[29] Gaebelein-Wissing N, Ellenbogen E, Lehmann P. Solar urticaria: clinic, diagnostic, course and therapy management in 27 patients[J]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges, 2020,18(11):1261-1268. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14309IF: 5.231 Q1 .

[30] Vergara-de-la-Campa L, Gatica-Ortega ME, Pastor-Nieto MA, et al. Vibratory urticaria-angioedema: further insights into the response patterns to vortex provocation test[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2020,34(11):e699-e701. doi: 10.1111/jdv. 16396.

[31] Fukunaga A, Oda Y, Imamura S, et al. Cholinergic urticaria: subtype classification and clinical approach[J]. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2022:1-14. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00728-6IF: 6.233 Q1 .

[32] Weller K, Groffik A, Church MK, et al. Development and validation of the urticaria control test: a patient-reported outcome instrument for assessing urticaria control[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2014,133(5):1365-1372, 1372.e1-6. doi: 10. 1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1076.

[33] Metz M, Ohanyan T, Church MK, et al. Omalizumab is an effective and rapidly acting therapy in difficult-to-treat chronic urticaria: a retrospective clinical analysis[J]. J Dermatol Sci, 2014,73(1):57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.08.011IF: 5.408 Q1 .

[34] Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Braido F, et al. A new tool to evaluate the impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life: chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire (CU-QoL)[J]. Allergy, 2005,60(8):1073-1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00833.xIF: 14.710 Q1 .

[35] Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use[J]. Clin Exp Dermatol, 1994,19(3):210-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.xIF: 4.481 Q1 .

[36] Koch K, Weller K, Werner A, et al. Antihistamine updosing reduces disease activity in patients with difficult-to-treat cholinergic urticaria[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2016,138(5):1483-1485.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.026IF: 14.290 Q1 .

[37] Ruft J, Asady A, Staubach P, et al. Development and validation of the Cholinergic Urticaria Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (CholU-QoL)[J]. Clin Exp Allergy, 2018,48(4):433-444. doi: 10.1111/cea.13102IF: 5.401 Q2 .

[38] Młynek A, Magerl M, Siebenhaar F, et al. Results and relevance of critical temperature threshold testing in patients with acquired cold urticaria[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2010,162(1):198-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09441.xIF: 11.113 Q1 .

[39] Ahsan DM, Altrichter S, Gutsche A, et al. Development of the cold urticaria activity score[J]. Allergy, 2022,77(8):2509-2519. doi: 10.1111/all.15310IF: 14.710 Q1 .

[40] Aguilera P. Inducing light tolerance with narrowband UV-B therapy in solar urticaria[J]. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed), 2018,109(10):853. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.06.009.

[41] Altrichter S, Salow J, Ardelean E, et al. Development of a standardized pulse-controlled ergometry test for diagnosing and investigating cholinergic urticaria[J]. J Dermatol Sci, 2014,75(2):88-93. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.04.007IF: 5.408 Q1 .

[42] Dressler C, Werner RN, Eisert L, et al. Chronic inducible urticaria: a systematic review of treatment options[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018,141(5):1726-1734. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018. 01.031.

[43] 中华医学会皮肤性病学分会荨麻疹研究中心. 中国荨麻疹诊疗指南(2018版)[J]. 中华皮肤科杂志, 2019,52(1):1-5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4030.2019.01.001.

[44] Maurer M, Fluhr JW, Khan DA. How to approach chronic inducible urticaria[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2018,6(4):1119-1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.03.007IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[45] He ZH, Qiu SC, Huang ZW, et al. Comparison between chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic induced urticaria on the efficacy of omalizumab treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Dermatol Ther, 2022,35(12):e15928. doi: 10.1111/dth.15928IF: 3.858 Q2 .

[46] Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations[J]. BMJ, 2004,328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490IF: 93.333 Q1 .

[47] Fialek M, Dezoteux F, Le Moing A, et al. Omalizumab in chronic inducible urticaria: a retrospective, real-life study[J]. Ann Dermatol Venereol, 2021,148(4):262-265. doi: 10.1016/j.annder. 2021.04.010.

[48] Maurer M, Schütz A, Weller K, et al. Omalizumab is effective in symptomatic dermographism-results of a randomized placebo-controlled trial[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017,140(3):870-873.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.042IF: 14.290 Q1 .

[49] Metz M, Schütz A, Weller K, et al. Omalizumab is effective in cold urticaria-results of a randomized placebo-controlled trial[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2017,140(3):864-867.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.043IF: 14.290 Q1 .

[50] Gastaminza G, Azofra J, Nunez-Cordoba JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab (Xolair) for cholinergic urticaria in patients unresponsive to a double dose of antihistamines: a randomized mixed double-blind and open-label placebo-controlled clinical trial[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2019,7(5):1599-1609.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.12.025IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[51] Aubin F, Avenel-Audran M, Jeanmougin M, et al. Omalizumab in patients with severe and refractory solar urticaria: a phase II multicentric study[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2016,74(3):574-575. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.021IF: 15.487 Q1 .

[52] Bonnekoh H, Terhorst-Molawi D, Buttgereit T, et al. Treatment of severe heat urticaria with omalizumab - report of a case and review of the literature[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2020,34(9):e489-e491. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16407IF: 9.228 Q1 .

[53] Rorie A, Gierer S. A case of aquagenic urticaria successfully treated with omalizumab[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2016,4(3):547-548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.12.017IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[54] Pressler A, Grosber M, Halle M, et al. Failure of omalizumab and successful control with ketotifen in a patient with vibratory angio-oedema[J]. Clin Exp Dermatol, 2013,38(2):151-153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04430.xIF: 4.481 Q1 .

[55] Can PK, Salman A, Hoşgören-Tekin S, et al. Effectiveness of omalizumab in patients with chronic inducible urticaria: real-life experience from two UCARE centres[J]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2021,35(10):e679-e682. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17385IF: 9.228 Q1 .

[56] Gorczyza M, Schoepke N, Krause K, et al. Patients with chronic cold urticaria may benefit from doxycycline therapy[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2017,176(1):259-261. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14820IF: 11.113 Q1 .

[57] Hannuksela M, Kokkonen EL. Ultraviolet light therapy in chronic urticaria[J]. Acta Derm Venereol, 1985,65(5):449-450.

[58] Levi A, Enk CD. Treatment of solar urticaria using antihistamine and leukotriene receptor antagonist combinations tailored to disease severity[J]. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, 2015,31(6):302-306. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12186IF: 3.254 Q2 .

[59] Borzova E, Rutherford A, Konstantinou GN, et al. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy is beneficial in antihistamine-resistant symptomatic dermographism: a pilot study[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2008,59(5):752-757. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008. 07.016.

[60] Maksimovic L, Frémont G, Jeanmougin M, et al. Solar urticaria successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulins[J]. Dermatology, 2009,218(3):252-254. doi: 10.1159/000193998IF: 5.197 Q1 .

[61] Kulthanan K, Ungprasert P, Tuchinda P, et al. Delayed pressure urticaria: a systematic review of treatment options[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2020,8(6):2035-2049.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.004IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[62] Kozaru T, Fukunaga A, Taguchi K, et al. Rapid desensitization with autologous sweat in cholinergic urticaria[J]. Allergol Int, 2011,60(3):277-281. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0269IF: 7.478 Q1 .

[63] Rujitharanawong C, Kulthanan K, Tuchinda P, et al. A systematic review of aquagenic urticaria-subgroups and treatment options[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2022,10(8):2154-2162. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.04.033IF: 11.022 Q1 .

[64] Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, et al. Natural course of physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema in 220 patients[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2001,45(3):387-391. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.116217IF: 15.487 Q1 .

[65] Bal F, Kahveci M, Soyer O, et al. Chronic inducible urticaria subtypes in children: clinical features and prognosis[J]. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 2021,32(1):146-152. doi: 10.1111/pai.13324IF: 5.464 Q1 .

[66] Dover JS, Black AK, Ward AM, et al. Delayed pressure urticaria. Clinical features, laboratory investigations, and response to therapy of 44 patients[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1988,18(6):1289-1298. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70137-1IF: 15.487 Q1 .

[67] Kim JE, Eun YS, Park YM, et al. Clinical characteristics of cholinergic urticaria in Korea[J]. Ann Dermatol, 2014,26(2):189-194. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.189IF: 0.722 Q4 .